Questions and answers about care for youth with gender dysphoria

What is gender?

What we call “gender” can be understood in many ways.

Gender identity is the gender you feel like. The gender you feel that you are. It doesn’t have to correspond with what your body looks like. All people have the right to decide what gender identity they have.

Gender expression is how you express your gender. You do that through for example clothing, body language, hairstyle, if and how you do your make-up and your voice. Gender expression is a part of your social gender. That has to do with for example interests, what role you play in groups and how you relate to different expectations based on gender.

Social gender can also have to do with how others perceive you.

Body refers to outer and inner genitalia, sex chromosomes and hormone levels; if you have ovaries, testicles, vagina, penis, highest levels of estrogen or testosterone, XX or XY chromosomes. It also refers to facial hair and other body hair and what your chest looks like. Biologically there are not only two genders, but a number of variations.

Legal gender is the gender that is registered in the population records. It’s in your passport and sometimes on your ID-card. Your legal gender is also manifested in the social security number’s next to last digit. There are two legal genders in Sweden: male and female. There are countries that have more legal genders, for example Germany, Australia and South Africa. In Sweden you are assigned your legal gender at birth by healthcare staff determining your gender based on outer genitalia.

What is gender dysphoria?

The National Board of Health and Welfare defines gender dysphoria as mental suffering or an impaired ability to function in your everyday life which is caused by your gender identity not corresponding with the legal gender you were assigned at birth. The person suffering from gender dysphoria can get gender affirming treatment.

The fact that you can diagnose someone with having gender dysphoria doesn’t mean that it’s a disease. The diagnose describes a need for contact with healthcare and some medical help. Read more about gender dysphoria as a diagnosis.

Many trans people have gender dysphoria, but there are also trans people who don’t. Gender dysphoria isn’t a a requirement for being trans, but a condition that often coincides with a gender identity that doesn’t correspond with the gender one was assigned at birth.

How does your gender identity develop?

Gender identity is formed very early. Already at just a couple of years old, children can determine that they have, or don’t have, the gender that society expects. Many live according to the gender that is expected of them and may experience a vague – but sometimes strong – feeling that something is “wrong” or hurts, but don’t have the words to describe it. Many trans people realise that they are trans during puberty, when physical changes and stronger gender norms make it more obvious that the assigned gender isn’t right. Some realise it as youth, some as adults and some later in life.

For some people the realisation that you are trans comes in the meeting with other trans people; you suddenly find the words to describe something you already feel but haven’t been able to express to yourself or others. For the great majority of people, gender identity is deeply rooted. For a small number of trans people gender identity is in flux, and you can identify as gender fluid and thereby have a changeable or fluid gender identity.

How do you get a gender dysphoria-diagnosis?

The possibility to access gender affirming care is very different in different countries. In Sweden, gender assessment and gender affirming care is a part of the public healthcare. In order to make sure that people get the right care, there are carefully conducted assessments, especially for people under 18. It’s important to understand that the Swedish trans care differs from for example American trans care, and that you therefore cannot apply American criticism or research on Sweden.

In Sweden, we conduct a so-called gender assessment with teams within specialist psychiatry at many university hospitals around the country. The queues to the assessment teams are often year-long, especially for people under 18. The assessment process for people under 18 takes many years to complete, for adults, it’s shorter. The assessment is done to find out if a person suffers from gender dysphoria and if gender-affirming care is right for the person in question. Just like in other assessments the teams investigate if there’s mental ill-health or other health problems that warrant treatment instead of, or before, gender-affirming treatment is started.

The gender assessment teams are made up of people who, apart from their professional skills, have expertise in gender dysphoria. The teams usually consist of a psychiatrist (a doctor specialised in psychiatry), psychologist and counsellor (social worker). There are other specialists tied to the team, such as an endocrinologist (hormone doctor), surgeon and a speech therapist (voice and communication specialist).

Just like in other assessments in psychiatry, a gender assessment is based on dialogue and standardised tests (most often in the form of forms that the care recipient fills out). The psychosocial assessment is an important part of the process. Here, the care recipient and the counselor map out the care recipient’s social network and what important people they have around them. In the gender assessments of children the child’s next of kin are involved. Not everybody who are diagnosed with gender dysphoria wants gender affirming treatment, but many people need some form of gender affirming treatment to lessen gender dysphoria.

Here you can read about the assessment process in more detail.

What type of gender affirming treatment can be given to children and youth?

Evidence based care

The care given to adults and youth with gender dysphoria follows national and international recommendations. The National Board of Health and Welfare has issued knowledge support about how the assessment and treatment of gender dysphoria in children should be conducted.

There are also protocols from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) for professionals in gender affirming care that state how the care should be administered, so called Standards of Care. Swedish healthcare should be be based on science and proven experience, in accordance with the healthcare act. Much research on the treatment of youth with gender dysphoria has been done in the Netherlands during the past few years, resulting in the “The Dutch Protocol”, which states that youth with gender dysphoria should be referred to a gender assessment team and have access to both psychological evaluations and treatments as well as somatic treatment if there’s a need for it.

Before puberty

If a child hasn’t reached puberty, assessment and medical treatment is delayed. Parents and children can receive occasional counseling and information about care that can be offered in the future. The main effort is to give support and help to parents, so that they will be able to support their child in developing in the way it wants to. For many children, no medical treatment is needed as they later turn out to identify with the gender they were assigned at birth.

During puberty

The assessment process takes multiple years for children and youth. If the youth expresses gender dysphoria during puberty, the doctor can make a preliminary gender dysphoria diagnosis. The youth can then receive puberty blockers (hormone blockers) that temporarily halts puberty during the course of the assessment. The puberty blockers that are used are the same as those that are given to children who enter puberty early, and where you want to postpone it for a few years. The puberty blockers are given to ease gender dysphoria but can also be used as a diagnostic tool to see how the person’s well-being is affected by taking the hormones.

The effect of puberty blockers is reversible and puberty will occur when the medication is stopped. Puberty blockers are prescribed for a limited amount of time. The medicine is considered safe but may, as all other medications, have side effects.

The teams work according to evidence-based international and national recommendations. If a person has other diagnoses, the assessment will take that into consideration. If gender dysphoria is present, a contrary hormone treatment can be started with androgen inhibitors, testosterone or estrogen. Treatments with irreversible effects, such as contrary hormone treatment or mastectomy, is generally not offered before an observation time of at least one year, and at 16 years old at the earliest.

18-year limit for genital surgery

Many trans people don’t need genital surgery and don’t want it. It is especially common among trans men to not undergo genital surgery, partly because the methods for creating a penis doesn’t deliver wanted results. You need to be 18 years old to get access to genital surgery and surgery that leads to infertility. Currently, people under 18 cannot get access to genital surgery in order to lessen gender dysphoria. If you are younger than 23, you need to have special circumstances. Other criteria must also be met and persons must apply to a special juridical council connected to The National Board of Health and Welfare for undergoing this surgery.

In the proposal of a new law about gender affirming genital surgery, it was suggested that people who have turned 15 but not 18 in individual, very rare, cases should be able to get genital surgery. This in cases where gender dysphoria is life threatening and the procedure should, according to the proposal, be approved by the National Board of Health and Welfare’s Judicial Council. Read more about what RFSL thinks about the proposal here. A later report, done by the The National Board of Health and Welfare in 2020, it was recommended to keep the age-limit of being at least 18 years old.

Why do more people seek gender affirming care?

The number of people seeking care

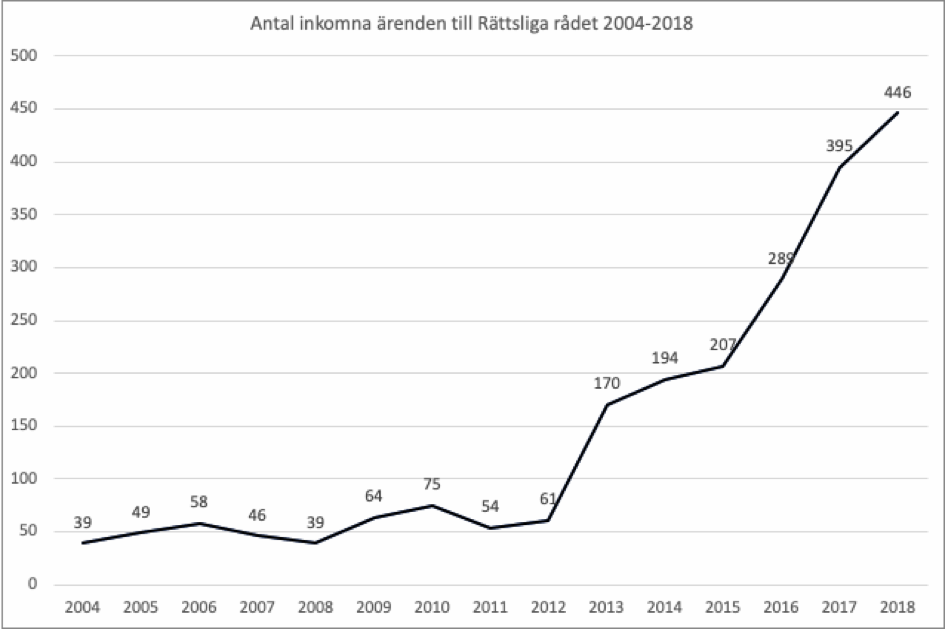

It’s difficult to get a picture of how many referrals come in to each gender assessment team, since each unit keeps its own statistics. The number of referrals don’t necessary reflect the number of people getting gender affirming care, as not everybody with a referral will need care or even show up for the first appointment. But there are statistics of incoming applications to the National Board of Health and Welfare’s Judicial Council and of the number of gender dysphoria diagnoses.

For a couple of years now, you have been able to write your own referral to some of the assessment teams, and more professions than ever are authorized to write a referral. It used to be very hard to get a referral to an assessment team, and this simplified procedure may partly be the explanation for the increased number of referrals.

Application to change legal gender

The number of cases with the National Board of Health and Welfare’s Judicial Council have increased over the last 15 years. In 2018 there were 446 applications and 441 decisions were made. Of these, 11 people were denied their application of a new legal gender. That means that 0,55 percent per 10 000 adults applied for a change of legal gender in 2018.

Image 1. The number of cases at the National Board of Health and Welfare’s Judicial Council per year. Source: Judicial Council.

The division of gender in those who apply is relatively even. 56 percent of those who applied in 2018, applied to change their legal gender to male.

1. You must be over 18 to apply for a change of legal gender.

Swedish legislation still demands that you go through a gender assessment investigation, are diagnosed with gender dysphoria and undergo gender affirming treatment before you can apply for a change of legal gender. RFSL wants the application for legal gender to be a separate process where you yourself decide your legal gender and can change it at the Swedish Tax Agency.

Image 2. The number of incoming cases, divided by gender, at the National Board of Health and Welfare’s Judicial Council. “Men” indicates people who apply for a new legal gender as male, and “women” indicates people who apply for a new legal gender as female. Source: Judicial Council.

Determined diagnoses of gender dysphoria

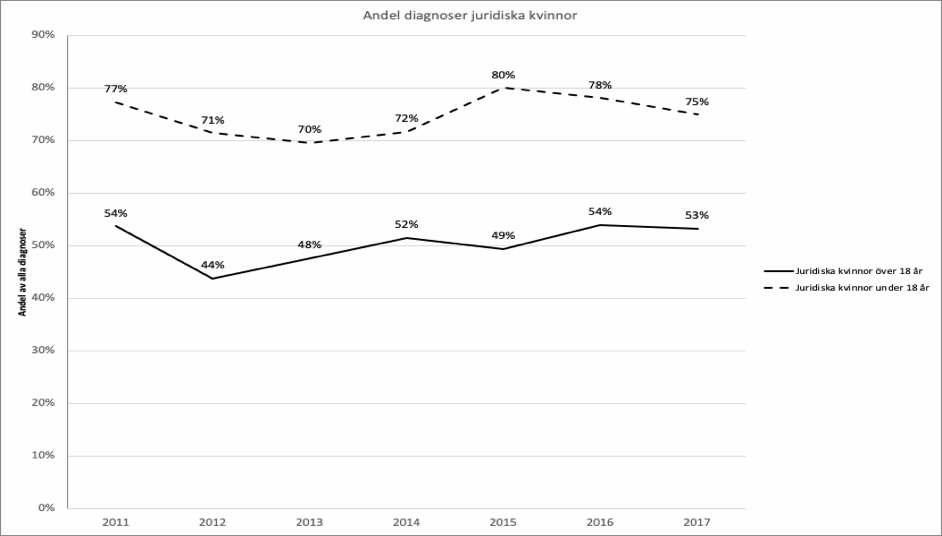

The number of diagnoses of gender dysphoria has increased over the last few years, both among adults and people under 18. In 2017, 957 people over 18 and 267 under 18 received the diagnosis. That means that 1,25 people under 18 per 10 000 children and 1,20 adults among 10 000 adult citizens were diagnosed in 2017.

2. Data before 2011 can not be divided between children and adults because the number of children is too low.

Image 4. The number of diagnoses among legal females for people under 18 and over 18 in 2011-2017. Source: The National Board of Health and Welfare.

The statistics show that about 50 percent of those who get their diagnosis when they’re above 18 are legal females, i.e. probably identify as men, trans men or non-binary. The same figure for people under 18 is 75 percent. The ratio legal males/legal females hasn’t changed much since 2011. Before 2011 the number of individuals is too low to support statistics about age.

More research is needed

Today we are witnessing an increase in the people who seek gender affirming care in all parts of the world where such care exists. The increased access to care, improved access to information about gender affirming care and that society has become more open to different identities and ways of being could partly explain this increase. Right now there are tendencies that the curve is flattening, meaning that the number of person’s is not increasing, but remaining the same from year to year. It is however to early to conclude that it actually is so and what it means.

The fact that more people seek care for gender dysphoria today compared to 10 years ago doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s an increase in people who suffer from gender dysphoria. More research has to be done to establish if this is the case. Research regarding why more people seek gender affirming care is on-going, but currently there is no clear consensus as to why. More research is also needed to understand why some groups display more gender dysphoria than others and are seeking care more frequently.

A change in care

Sweden has offered care to people with gender dysphoria since the 1960s. However, until 2010 the accessibility and knowledge about the care was very limited. In 2010 the National Board of Health and Welfare published a report about care in gender dysphoria. The report stated that many people who were in need of care didn’t get it since the gender assessment investigation didn’t always focus on the individual’s needs. In order to get gender affirming treatment you had to live up to a certain image of what it meant to be a trans person, and you were expected to want all treatments that were available. Openly non-binary people only gained access to gender affirming care in 2010, and then only to a limited extent.

In 2015 the National Board of Health and Welfare published knowledge support for care in gender dysphoria. New norms about who could get care and what type of care should be offered were established. Nowadays it’s more widely known that non-binary people can access gender affirming care, but care is seldom given to people under 18. It’s also easier to get information about that you can start a gender assessment process and get treatment before 18. The number of gender assessment teams that accept referrals from people under 18 has increased. It’s now also possible to write your own referral to some of the assessment teams and more professions than before have the authority to writing a referral. Earlier, it was very hard to get a referral to a gender assessment team, so a simplified procedure can partly explain the increase in referrals.

The law has changed

The possibility of changing legal gender was more limited in 2013 than it is today. Until 2010 you had to be unmarried to change your legal gender. Until 2013 you could only change your legal gender if you were a Swedish citizen. You also had to be sterile to change your legal gender, and you were prohibited from saving gem cells.

These demands and limitations kept many from seeking gender affirming care, or led to that they didn’t get care even though they asked for it. When the forced sterilisations were stopped, the number of applications for changing legal to the National Board of Health and Welfare’s Judicial Council almost tripled (from 61 applications in 2012 to 170 applications in 2013). Many people within the gender affirming care had probably waited to apply for a change of legal gender until the demand for sterilisation was removed.

How do people feel after gender affirming treatment?

Care lessens the suffering of gender dysphoria

Research shows that most people who have gone through a gender affirming treatment experience greater gender congruence, i.e. that the body and the gender identity are a better match. The psychological suffering and the everyday difficulties that are caused by gender dysphoria lessen as gender dysphoria is decreased.

For people in puberty the need for care can increase as the body changes. This can be avoided if you get the right care in time. Read more about this in Läkartidningen.

Mental ill-health

People who break norms regarding gender and sexuality are affected by minority stress. According to researchers, minority stress is the single most important explanation of why mental ill-health is more common among trans people than in the population at large. But it’s important to remember that far from all trans people are affected by mental ill-health. What we can see is that more trans people have experienced mental ill-health compared to the population in general.

The suffering of gender dysphoria in most cases decreases with gender affirming treatment, but if you at the same time are suffering from depression, anxiety or an eating disorder that usually requires separate treatment. Support and treatment for people who suffer from different types of mental ill-health during and after their gender assessment process needs to be increased. Many also report that the long waiting times for a gender assessment investigation and gender affirming treatment are very mentally taxing. The minority stress that comes after a transition, when people might question you and when you have to come out and be confronted with trans phobia etc., also affects well-being.

Mental ill-health can also arise from bullying in childhood or other factors that have nothing to do with gender dysphoria. This ill-health often remains after gender affirming treatment and may need to be processed.

Suicide

In 2020 the first report on suicide and gender dysphoria in Sweden was made. This was done by looking at diagnostic codes over a span of 20 years. The report doesn’t cover all trans persons who has died by suicide in this period: only the persons that has been in contact with a gender dysphoria team and gotten a gender dysphoria diagnosis. The report shows that persons with a gender dysphoria diagnosis have a higher risk at dying in suicide compared to persons in general. Trans women had a 4,9 higher risk and trans men 13,7 higher risk at dying in suicide compared to the average. The report also concluded that the persons that had died in suicide also had several other psychiatric diagnoses. As in all other suicides, there is an interaction between several factors. The report can be found at The National Board of Health and Welfare.

All reports about suicidal thoughts and attempts at suicide show that these are more common among trans people than in the population in general. Several reports show that about a third of all trans people have attempted suicide at some point of their lives. Different studies also show that the number of trans people who have attempted suicide during the past year is high; about five times as high as in the population in general (5 percent of trans people compared to 1 percent of the population in general).

Preliminary figures from the Norwegian investigation Kjønn, helse og medborgerskap show that access to gender affirming treatment can be related to a lower risk of suicide. Preliminary figures from the investigation show that 90,8 percent of the trans people who have attempted suicide and undergone gender affirming treatment made their attempts before the treatment was started. The number of attempted suicides during and after treatment is 12,6 and 5,0 percent respectively.

Even though gender affirming treatment, as afore mentioned study shows, has positive effects, research shows that many people who have undergone gender affirming treatment suffer from mental ill-health and that there’s still an increased risk of suicide compared to the population in general. This is most likely because many trans people have experienced difficulties in their lives and have a heightened vulnerability to minority stress. Gender affirming care does play an important role in promoting good mental health and decreasing suicidal thoughts and attempts at suicide among trans people, but there are other areas that need to be investigated further in order to decrease suicidal thoughts and attempts at suicide.

The need for care for people experiencing puberty may increase as the physical changes become more apparent, something that in many cases can be avoided if the person gets care in time. Read more about this in Läkartidningen.

What happens if you change your mind or get misdiagnosed?

How common is it to change one’s mind or get misdiagnosed?

It is very rare for people who have undergone gender-affirming treatment to have regrets, in the sense of wanting to change back to their legal gender or reverse the effects of surgery or hormones. Gender assessments in Sweden are thorough and include a psychosocial assessment and work with realistic expectations of the results of treatment in order to exclude as far as possible the risk of regret or misdiagnosis.

The Swedish research shows that the percentage who regret their change of legal gender is very small (0.2 percent between 2000 and 2010) and has decreased over time. SBU, the State’s Committee for Medical and Social Evaluation, has recently published a knowledge overview in which they went through 47 different studies that have been done around regret and detransition , most of them outside of Sweden. Since there is great variation between the existing studies, it is difficult to say exactly how many regret, have been misdiagnosed or detransitioned, but the collected studies show that between 0-4% have experienced regret in some way. It includes both regret over results from treatment and regret over having undergone treatment. The studies also show that between 1-13% detransitioned in whole or in part. Some have regretted their transition and/or have returned to identifying with their assigned gender, but the studies also describe people who detransitioned due to social factors without changing their gender identity, or who, for example, went from a binary to a non-binary gender identity. RFSL sees a need for more studies in a Swedish context around regret and detransitioning, especially with a focus on what support is needed and how gender-affirming care can be improved.

What is regret

The word “regret” can be understood in different ways and is often used carelessly in the context. It can be about regretting your entire gender-affirming treatment, but it is more common to regret a specific surgical procedure or the result of it. You can e.g. regret treatment because you did not get the results you needed, or because you had complications after treatment. Regret about hormone therapy also occurs but is less common.

Sometimes regret is instead, for example, about anger or sadness in the case of wrong treatment or forced sterilization. It could be that you underwent genital surgery because you felt pressured to do so, not because you actually had a need. People who have been forcibly sterilized may feel remorse for undergoing the operation, but had no choice but to agree to it. Care was much stricter 10-20 years ago, but is today more individually adapted.

“Regret” can be a loaded word. In cases where you have been misdiagnosed, the responsibility lies with the care. The same applies if you underwent treatment because the care had compelling expectations of you or because there were actual demands for certain treatments. If you regret part or all of your treatment, healthcare should help with new treatment that feels more right.

Other words, which may be more accurate for some, are that you are dissatisfied with the care or with the results of the treatment you have received. Please read more about this on our website Transformering

When gender affirming treatment isn’t the right thing

The gender assessment process is constructed to determine if a person experiences gender dysphoria and if gender affirming treatment is suitable. That means that some people during the course of the investigation will reach the conclusion that gender affirming care isn’t right for them. This is not the same as changing one’s mind, but rather a result of the assessment that is equally as important as reaching the conclusion that one is in need of gender affirming care. This just means that the assessment is filling it’s function.

To terminate treatment with puberty blockers

If you want to terminate treatment that you have started you can get help from trans care. If you’ve been prescribed puberty blockers and don’t want to take gender contrary hormones (testosterone or estrogen), you can terminate the treatment. Your body will then enter into puberty by itself.

To regret permanent effects

In the small number of cases where someone has received gender affirming treatment with irreversible effects (for example gender contrary hormone treatment or surgery) and regret the treatment, you get help from the assessment team to change the body again using the methods available. The team can also provide psychological support to some extent.

That someone regrets a physical transition can lead to psychological suffering, just like other mis-diagnosed conditions and wrongful treatments can cause suffering. Regardless of how few people regret gender affirming care, the ambition should always be to rule out the risk of mis-diagnosis and wrongful treatment, and doing this without prolonging the suffering by delaying care for those who are in need of gender affirming care.

More research about people who regret undergoing gender affirming care is needed in order to investigate the reasons why and be able to avoid such issues in the future. People that have regretted their gender affirming treatment are free to contact RFSL for support or to share their story. We have e-mail support for people with trans experience.

What is the Rapid-onset gender dysphoria theory?

Rapid-onset gender dysphoria (ROGD) is a theory formulated by researcher Lisa Littman based on a survey of 256 parents to trans children, mainly in the US and Great Britain. The theory describes gender dysphoria as something “contagious” that “breaks out” in groups of friends in their teens or as young adults, and which is also spread via internet. Littman’s results were published in an article in PLOS ONE in August 2018. March 19, 2019, Littman had to publish a clarification and altered conclusions of her research in PLOS ONE because of criticism from other researchers.

Littman’s study has received harsh criticism. Among other things because the parents who answered the survey were recruited mainly in forums for parents who were skeptical and negative towards their children’s gender identity and gender dysphoria. It wasn’t a representative selection of parents of youth with gender dysphoria. Littman didn’t ask the youth any questions, but talked only to their parents. 76 percent of the respondents believe that their children aren’t trans, 2,4 percent believe their child. This shows that the study is based on results from parents who have a negative view on their children’s gender identity.

A common denominator for the parents in Littman’s study appears to be that they’ve never suspected that their children were suffering from gender dysphoria or identified themselves as anything other than the gender they were assigned at birth before they came out. “Rapid onset” means that the parents suddenly found out about their child’s gender identity or gender dysphoria, rather than that the gender identity or gender dysphoria developed suddenly.

It’s very common that gender dysphoria manifests in the teenage years or increases in puberty. This is nothing new. It’s well known through research and medical practice that gender dysphoria often manifests or is intensified during puberty, or later.

RFSL and RFSL Ungdom are critical to Littman’s study and the term ROGD. Our view is that children’s as well as adults’ gender identity and reflections on gender should always be respected in a way that feels secure for the individual. It’s up to the specialist multi disciplinary teams that work with assessments and treatment of children with gender dysphoria to determine if the gender dysphoria is lasting or not and what kind of treatment could be beneficial to the child. It’s important that trans people are met with respect and acceptance.

WPATH, World Professional Association for Transgender Health made a statement about ROGD in September 2018. WPATH underscores the need for more research about gender identity and criticizes the term RODG. They write:

… [it is] both too early and inappropriate to use seemingly scientific labels that make clinics, members of the community and researchers draw definite conclusions about the development of gender identity in youth, and about the factors that may affect at what time a young person chooses to disclose that ze is of a different gender than the one they were assigned at birth.

How does RFSL and RFSL Ungdom believe that trans care can be improved?

RFSL and RFSL Ungdom believes that the gender affirming care can be improved in many areas. A few examples are easier referral systems, shorter waiting times and equal care across the country. Gender assessment teams need more resources and, as do units that work with gender affirming treatment, for example surgical units and hair removal clinics.

Research and follow-up

There should be systematic follow-ups of people who have undergone gender assessment investigations and gender affirming treatment in order to be able to map out areas that could be improved and to offer support after a gender assessment investigation and possible gender affirming treatment. RFSL welcomes the gender dysphoria register that’s been instated. The purpose of the register is to follow up on the care given to people who go through a gender assessment investigation and get gender affirming treatment.

More research about gender affirming care is needed, among other things about the reasons why some people choose to terminate a gender assessment investigation or regrets gender affirming treatment. It needs to be investigated if there are reasons to terminate an assessment/treatment other than that the person themself realizes that they don’t want gender affirming care (for example threats or harassment from family members, worries about social exposedness etc.). The assessment teams need to be tasked with doing follow-up and be given the resources to do it.

Non-binary youth

The gender affirming care for children and youth with gender dysphoria, and especially the care for non-binary youth, needs improvement. Today, non-binary people under 18 can be denied gender assessment and gender affirming treatment. Several clinics don’t even offer counseling to youth who are non-binary. Instead they have to wait until they turn 18 until they can get support and an assessment. We believe that everybody who experiences gender dysphoria has the right to care. Gender dysphoria manifests itself similarly for all who experiences it, regardless of trans identity. Care should focus on decreasing gender dysphoria, regardless of trans identity.

Improved support

RFSL and RFSL Ungdom also believe that the support for both the care recipient and their next of kin should be increased through the assessment teams getting more resources. All care recipients should have access information that is tailored to their age and needs. People under 18 should, which is also the National Board of Health and Welfare’s recommendation for care of children, have access to a contact person during the gender assessment and gender affirming treatment to safeguard that the child’s perspective is respected.

Increased knowledge about gender identity and trans

We also believe that all children and youth have the right to correct and relevant information about gender identity and trans. It should be self evident that grown-ups children meet in their everyday life – in pre-school and elementary school, in high-school, at youth clinics, BUP and other places – provide for this need. Knowledge about gender dysphoria and gender identity must be mandatory in educations to do with care. It is central to trans people’s health to be met with respect and have your gender identity acknowledged by caregivers, school and other authorities.

RFSL and RFSL Ungdom’s opinion on the 18 year limit for genital

RFSL and RFSL Ungdom welcome the proposal to abolish the existing legislation and instead instate two separate laws: one for changing legal gender and one for having gender affirming genital surgery. Both these measures are crucial for trans people’s health. Read our statement of opinion here.

It’s important to remember that very few trans people under 18 are in need of genital surgery, and many will choose not to do it even further down the road.

The proposition of a new legislation on genital surgery stated that people who have turned 15 but are not yet 18 in rare cases can qualify for such treatment. The proposition affects a few cases where gender dysphoria is life threatening and the operation should, according to the proposition, be approved by the National Board of Health and Welfare’s Judicial Council. RFSL believes that legislation shouldn’t get in the way of vital care. The assessment team’s task is to determine who suffers from gender dysphoria and for which people gender affirming treatment is the right way to treat the suffering. It’s always up to the caregiver to follow the healthcare act, i.e. to provide care that is based on science and experience. RFSL feels that specialists in trans care, in dialogue with the care recipient, should determine what care the care recipient needs.

Doctors have, together with the patient, the opportunity to decide what kind of care a patient needs and then to start treatment. It’s reasonable that the care for young trans people should work in the same way, without legislation limiting the opportunity for necessary care. Some doctors have been skeptical of removing the prohibition for genital surgery in people under 18, for worry that premature operations should be made. However, doctors make, together with their patients and next of kin, vital decisions everyday, and we don’t believe that a special legislation that prevents doctors from making these decisions is necessary. We are convinced that doctors will be very restrictive in making irreversible operations on the genitalia of minors unless they are convinced that the decision is deeply rooted in the care recipient and that the risk of regret is minimal. The child’s well-being should always be the most important thing.

Who can I talk to if I have more questions?

You can read more at Transformering.se and e-mail Transformering here, there’s information for you who are trans or unsure of your gender identity, regardless of your age. The website and the e-mail is also targeted at you who are close to or meet trans people in your profession.

Press: If you have questions about RFSL and RFSL Ungdom’s policys or advocacy work, contact press@rfsl.se or info@rfslungdom.se

Sources and tips for further reading

God vård av barn och ungdomar med könsdysfori. Nationellt kunskapsstöd (Socialstyrelsen 2015)

God vård av vuxna med könsdysfori. Nationellt kunskapsstöd (Socialstyrelsen 2015)

Metodbeskrivning och kunskapsunderlag för respektive kunskapsstöd finns tillgängligt på Socialstyrelsens hemsida: socialstyrelsen.se/konsdysfori

Till dig som möter personer med könsdysfori i ditt arbete (Socialstyrelsen 2015)

Utvecklingen av diagnosen könsdysfori. Förekomst, samtidiga psykiatriska diagnoser och dödlighet i suicid (Socialstyrelsen 2020)

https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2020-2-6600.pdf

Transsexuella och övriga personer med könsidentitetsstörningar. Rättsliga villkor för fastställelse av könstillhörighet samt vård och stöd (Socialstyrelsen 2010)

”Barn under 18 år som söker hälso- och sjukvård” (Socialstyrelsen 2010)

https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/18100/2010-8-3.pdf

Utvecklingen av diagnosen könsdysfori i Sverige (Socialstyrelsen 2017) http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/20656/2017-7-2.pdf

”Könsdysfori ökar – särskilt bland unga” (Socialstyrelsen 2017)

http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/nyheter/2017/konsdysforiokarsarskiltblandunga

”’In society I don’t exist, so it’s impossible to be who I am.’ Trans people’s health and experiences of

healthcare in Sweden” (RFSL 2017)

”Chosen name use is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among transgender youth” (Russell m.fl. 2018)

”Kraftig ökning av könsdysfori bland barn och unga. Tidigt insatt behandling ger betydligt bättreprognos” (Frisén m.fl. 2017)

http://lakartidningen.se/Klinik-och-vetenskap/Klinisk-oversikt/2017/02/Kraftig-okning-av- konsdysfori-bland-barn-och-unga/

Outcome and refinements of gender confirming surgery (Hannes Sigurjónsson, Karolinska Institutet 2016)

”Transsexualism: treatment outcome of compliant and noncompliant patients” (Pimenoff & Pfäfflin 2011)

”Long-term follow-up of adults with gender identity disorder”(Ruppin & Pfäfflin 2015)

”A five-year follow-up study of Swedish adults with gender identity disorder” (Johansson m.fl. 2010)

On Gender Dysphoria (Cecilia Dhejne, Karolinska Institutet 2017)

Könsdysforiregistret, https://konsdysforiregistret.se/

”WPATH POSITION ON ’Rapid-Onset Gender Dysphoria (ROGD)’” (World

Professional Association for Transgender Health, 2018) https://www.wpath.org/media/cms/Documents/Public%20Policies/2018/9_Sept/WPATH%20Positio

n%20on%20Rapid-Onset%20Gender%20Dysphoria_9-4-2018.pdf